According to a BBC article, in October last year Prime Minister Boris Johnson shared a widely misunderstood statistic comparing the median age at death of COVID fatalities to population life expectancy, with the suggestion “get COVID and live longer”.

On the surface this might seem like a reasonable comparison – so why is it inappropriate?

The data on the median age of COVID fatalities was about right at the time. Vaccines subsequently reduced this as high uptake among the oldest lives means they now have better protection.

However, the comparison made here is between median age at death and period life expectancy at birth. That is a poor comparison for a number of reasons – in order of increasing importance:

- Life expectancy is a mean, not a median

- Life expectancy at a given age generally increases over time

- Life expectancy increases as we age

I’ll briefly explore each in turn.

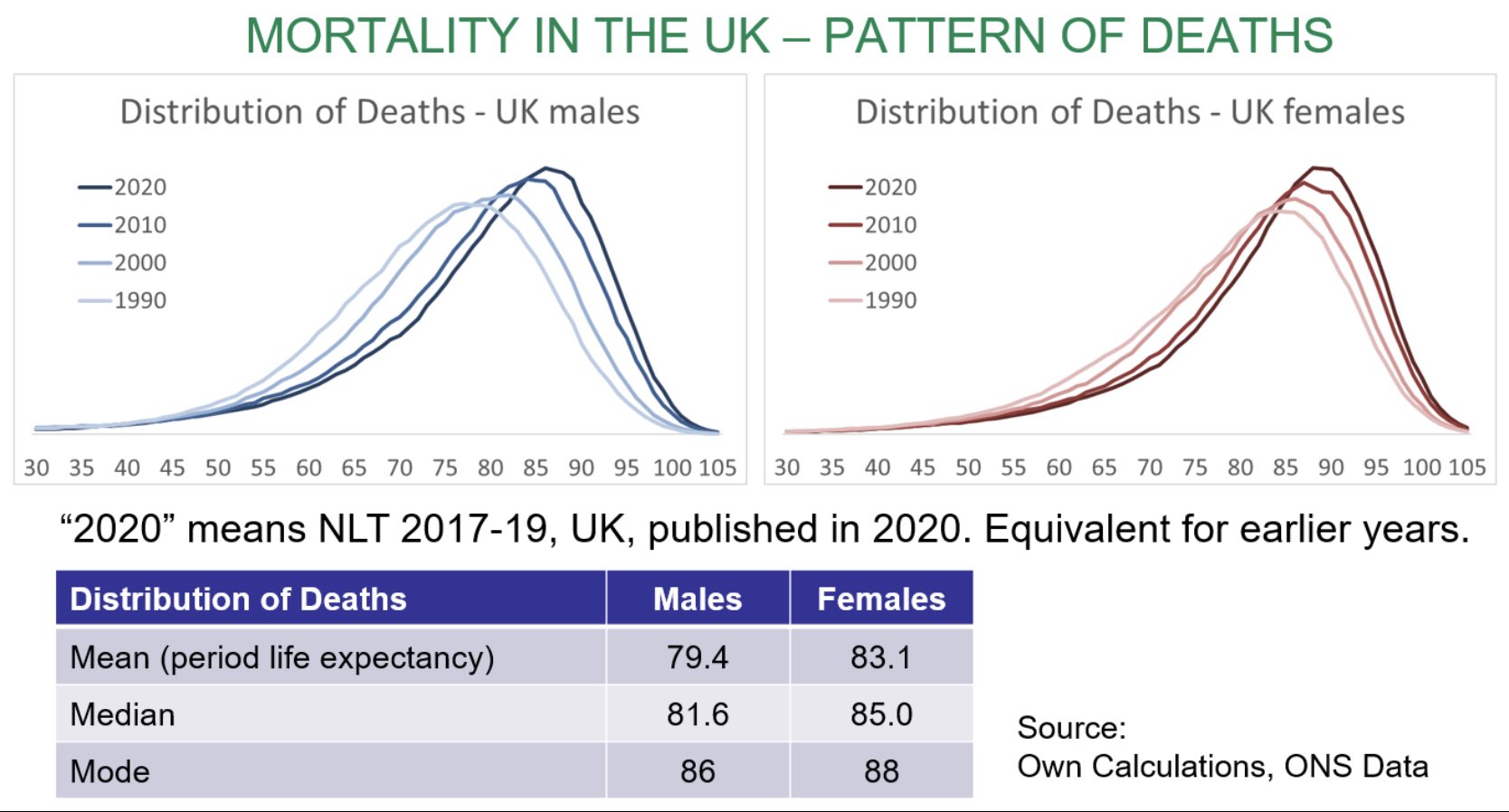

Median versus Mean

The distribution of life expectancy is skewed because it’s much more likely that someone dies decades before their life expectancy than decades after (i.e. if life expectancy is 90 you are more likely to die aged 60 than aged 120). This means that most people live longer than their life expectancy – the median exceeds the mean by around two years. It is inappropriate to compare the median COVID death to (mean) life expectancy.

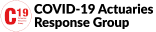

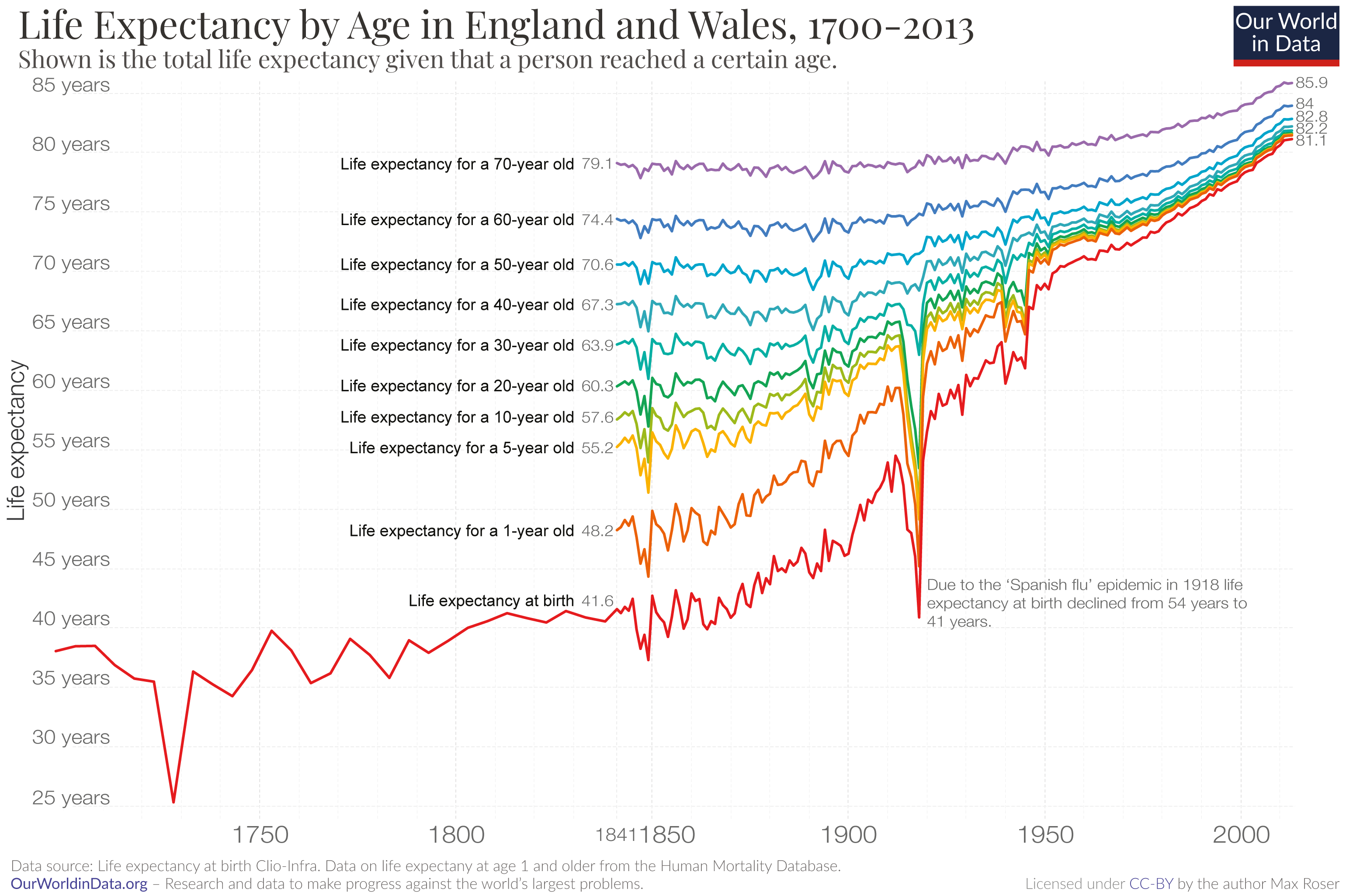

Life Expectancy increases over time

Medical, nutritional, lifestyle and other changes in society mean that death rates tend to fall over time, leading to increases to life expectancy. It is of course possible for death rates to stagnate, or even increase, but in almost all countries at almost all points in the last 200 years life expectancy has been increasing. In the UK for example, life expectancy was increasing by around three months each year during the 2000s.

“Period Life Expectancy”, as seemingly used in the above comparison, makes no allowance for future changes to death rates. A better measure of how long we can expect to live is “Cohort Life Expectancy”. Cohort life expectancy typically exceeds period life expectancy by a few years (exactly how many depends how quickly death rates are expected to fall). It was inappropriate to compare median age of COVID deaths to period life expectancy.

Life expectancy increases as we age

As noted above, life expectancy is an average, and gets dragged down by those who sadly die young. This introduces a survivorship effect whereby life expectancy is higher for those who have already attained a given age. Put simply, life expectancy at age 80 is much higher than life expectancy at birth because we know that the person lives for at least 80 years.

The chart below from Our World in Data gives a great illustration of the way life expectancy varies by age and over time.

Conclusion – Get COVID and Live Longer?

It should now be clear that you can’t “get COVID and live longer”. The real impact of COVID on life expectancy is unknown..

So if we put this all together, what is a more appropriate comparison?

The Office for National Statistics provides a simple tool which allows us to check our cohort life expectancy at any age. This is a better indication of how long we can expect to live.

We can see that at age 80, life expectancy is 9 more years for a male and 10 more years for a female. At age 90, life expectancy is 4 more years for a male and 5 more years for a female.

In summary, the comparison apparently cited by the Prime Minister in October last year was inappropriate.

You can check your own life expectancy here: