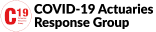

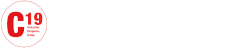

In January 2021, the journal Nature asked more than 100 immunologists, infectious-disease researchers and virologists working on the coronavirus response whether it could be eradicated. Almost 90% of respondents think that the coronavirus will become endemic.

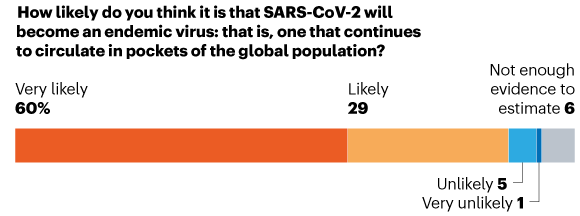

In answer to a question on whether the virus can be eliminated from some regions, the survey revealed a mixed response but more than half of respondents thought an elimination scenario to be unlikely.

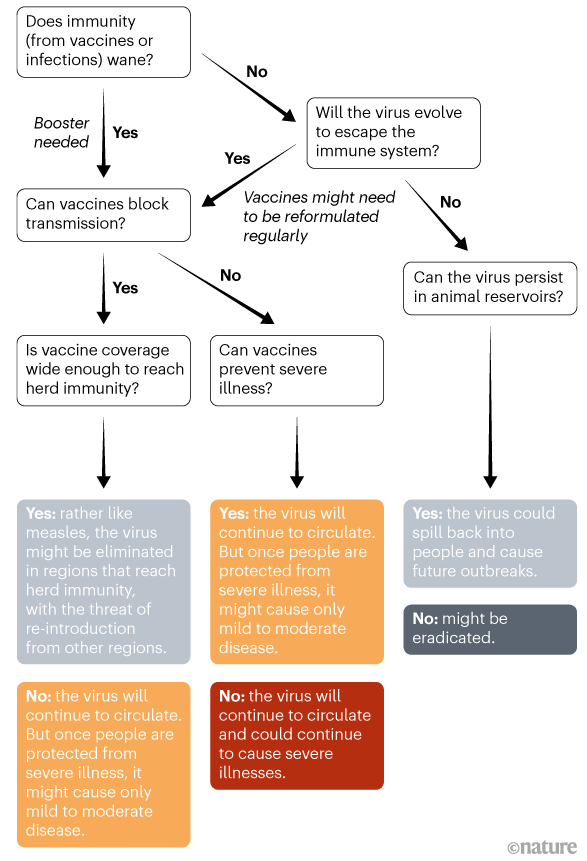

In the same survey, respondents were asked about the key factors that are likely to contribute to the eventual endemic state of the virus. In the next figure, we can see that this very much depends on immunity levels, variants and vaccines.

Out of these, waning immunity was thought to be one of the main drivers of the virus becoming endemic, as opposed to being eradicated through herd immunity. However, endemicity does not necessarily mean that the virus will continue to exert the lethality that we have unfortunately experienced until now.

Other circulating coronaviruses are endemic, probably have been for hundreds of years and are responsible for around 15% of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). Indeed, it is suggested that COVID-19 may become a disease first encountered in childhood, causing mild cold-like symptoms. Immunity generated by vaccination and/or previous infection could be enough to prevent severe infection in adults; the timeline for this, however, is still unknown and may largely depend on population demographics.

One school of thought is that the 1889-1890 pandemic, sometimes known as the Asiatic or Russian flu — which killed one million people, primarily adults over age 70 — may have been caused by the emergence of HCoV-OC43 virus, which is now an endemic, mild, repeat-infecting cold virus affecting mostly children aged 7-12 months old.

As previously discussed, waning immunity could be the biggest challenge which may necessitate a regular vaccination programme, though it is too early to say with any certainty whether it will be an annual programme like that for influenza, or a less frequent booster.

Analysis by McKinsey sets out some key themes around the potential endemic future of SARS-CoV-2. It is suggested that endemicity is a more realistic endpoint than herd immunity, and one of the starting points on this road has to be shifting focus from case counts to managing severe illnesses and deaths. The Delta variant, for example, has pushed the potential of reaching herd immunity in some populations ever further out of reach.

An endemic future may include localised outbreaks, with serious illness only occurring in unvaccinated people. The world could fall into three broad categories going forward:

- High vaccination countries.

- Case controllers (countries that have kept case counts low with tight border restrictions and a strong public-health response to imported cases, and where border re-opening and future cases are contingent on vaccine roll out).

- At-risk countries (most lower-income and many middle-income countries that have had insufficient access to vaccines and remain at risk of significant waves of disease).

A Lancet publication describes that what emerges next “will partly depend on the ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2, on the behaviour of citizens, on governments’ decisions about how to respond to the pandemic, on progress in vaccine development and treatments and also on a broader range of disciplines in the sciences and humanities”.

A number of possible future scenarios have been proposed. Publishing in Nature, a team of academics outline three key possible futures:

- Ongoing manifestations of severe disease, infection and variant emergence requiring worldwide application of vaccines, disease surveillance and accurate testing.

- An epidemic seasonal disease, similar to influenza, with effective treatments such as monoclonal antibodies to reduce the hospitalisation and mortality burden.

- Transition to an endemic disease, much like the existing circulating coronaviruses, with minimal impact on mortality.

However, many unanswered questions mean that we are still unable to predict with any confidence the likelihood of any of these scenarios emerging. What we can and must do is examine in more detail how each of these scenarios may play out in order to be better prepared for what comes next.