The WHO designated B.1.1.529 a Variant of Concern on 26 November 2021. This happened a mere two days after the existence of this variant was announced. The variant was assigned the Greek letter Omicron, which literally means “little O”. The WHO based its decision to classify Omicron as a Variant of Concern on several mutations that may have an impact on how easily it spreads, or the severity of illness it causes.

Little is known about this variant’s characteristics because of the recency and speed of its emergence. In this blog we set out what is known, as well as what is still to be determined and when and how this information may become available. We also suggest how to think about next steps against this backdrop of uncertainty.

On 28 November, the WHO released a statement setting out what was known at the time about:

- Transmissibility

- Severity of disease

- Effectiveness of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection

- Effectiveness of vaccines

- Effectiveness of current tests

- Effectiveness of current treatments

The WHO was confident that PCR tests and treatments with corticosteroids and IL6 Receptor Blockers would still be effective. On all other points they stated that the evidence was not yet clear.

Since then further information has become available.

Transmissibility

We do not know the value of R0, the basic reproduction number. We can observe the recent effective reproduction number (Rt) associated with Omicron. This will be influenced by any existing immunity. Any precautions taken to reduce infections also influence Rt.

In South Africa, which was one of the first countries where Omicron was detected, Rt is currently estimated to be about 2. Rt was below 1 until early November. Mobility levels are at or above pre-pandemic levels. Measures such as mask-wearing still remain in place. The South African vaccination status dashboard shows that 48% of the population aged 18 or older had received at least one vaccination dose by 6 December 2021. This information, along with the rate at which Omicron has replaced Delta among cases sequenced in South Africa, suggests that Omicron has a transmission advantage over Delta.

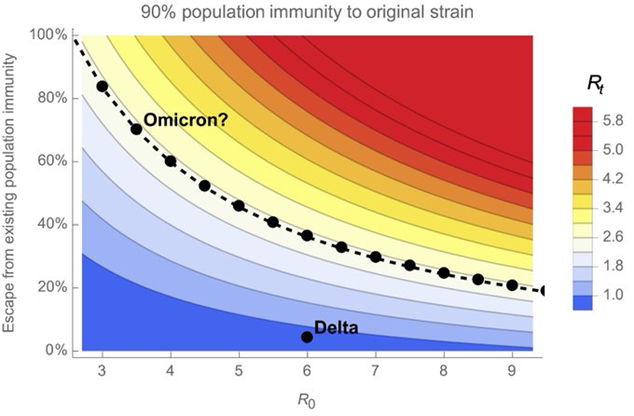

Using the information about Rt, and assuming that 90% of the South African population has some form of prior immunity, Trevor Bedford has shown the interplay between R0 and escape from this immunity. Where there are low levels of immunity escape, a high R0 value is needed to arrive at an observed Rt value of between 2 and 3. Conversely, a low R0 value implies more significant immune escape.

There is of course a third factor that could contribute to faster spread, namely the serial interval (the time between successive cases). For Delta, estimates ranged from 2.3 to 3.3 days. Anecdotal reports suggest a further shortening for Omicron, but these could be highly misleading given that the serial interval can vary widely between people. We illustrate this effect with an example. Given an effective Rt of say 4, a serial interval of 2.3 would result in roughly four times as many infections in a week than would a serial interval of 3.5. So, a modestly shorter serial interval can ramp up growth quite substantially.

437 Omicron infections have been reported in the UK by 7 December. The doubling time is said to be 2 to 3 days. This is similar to the ~2.5 day doubling time observed between 13 February and 12 March 2020 in the UK, though that was in a fully susceptible population and with little change at the time from baseline mobility.

Severity of Disease

The South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) reported on early experience of admissions at a hospital complex in the Tshwane metropolitan area. This is where the Omicron outbreak took hold earliest. There were 166 new admissions between 14 and 29 November which represents the first two weeks of the Omicron wave. Among the majority of these admissions, COVID was an incidental finding.

A snapshot of 42 patients on 2 December showed that 28 were not oxygen-dependent. Of 14 patients on oxygen, only 9 were on oxygen because of COVID. This differs from previous waves when the majority of patients did require oxygen.

Out of the 166 admissions, 10 patients have died so far. The number of deaths in this cohort may still increase among patients who remain in hospital. The in-hospital fatality rate in previous waves was 23%.

These initial findings suggest that Omicron may have less severe impacts than were seen for other variants. The SAMRC states that it will take another two weeks before one can draw more precise conclusions about disease severity.

Effectiveness of prior infection-acquired immunity

The hazard ratio for reinfection versus primary infection in South Africa in November was 2.39 (CI95: 1.88–3.11), according to a pre-print study by Pulliam et al. The authors conclude that “population-level evidence suggests that the Omicron variant is associated with substantial ability to evade immunity from prior infection. In contrast, there is no population-wide epidemiological evidence of immune escape associated with the Beta or Delta variants.” Since the start of the pandemic, 35,670 suspected reinfections have been identified among 2.8 million South Africans with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Effectiveness of vaccine-acquired immunity

The Tshwane hospital snapshot on 2 December shows a split by vaccination status. Of 38 adults, 6 were vaccinated, 24 were unvaccinated and vaccination status was unknown for 8 patients.

80% of admissions between 14 and 29 November were below age 50. This age profile may have been influenced by age patterns of infections as well as age profile of vaccination status. Around 50% of adults in Gauteng, the province where Tshwane is located, were vaccinated by end of November, but this figure drops to below 25% for adults below age 35.

Based on these very small numbers, there may be a signal that vaccines have been protective, however caution is needed because of possible confounding with the age pattern of infections.

Effectiveness of prior infection and/or vaccine-acquired immunity

On 7 December, the first results looking at neutralising antibodies under laboratory conditions were released. These experiments entail looking at how many times a blood sample can be diluted and still inhibit virus from growing in cell culture.

Research from the Africa Health Research Institute was based on plasma samples from 12 participants. Six participants had been vaccinated with Pfizer-BioNTech only. The other six were vaccinated in addition to being previously infected. The study compared the ability of these plasma samples to neutralise live Omicron virus with ability to neutralise the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 virus (D614G or wild type). On average a 41-fold loss in Geometric Mean Titre was observed. The researchers found that Omicron escapes antibody immunity induced by the vaccine, but that considerable immunity is retained among people who were both vaccinated and previously infected.

Preliminary results from a Swedish study showed a 7-fold reduction in neutralisation potency for Omicron compared to wild type SARS-CoV-2. The study used blood samples from 17 participants and was based on pseudovirus rather than live virus, which is safer to handle and allows laboratories with less stringent safety standards to perform experiments.

Preliminary results from a German study were also shared on 8 December. The study investigated impact on neutralisation among blood samples of people vaccinated with varying numbers of doses of Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and AstraZeneca vaccines. Results were compared between Omicron and Delta. Up to 37-fold reduction in neutralisation was observed, even in the presence of a third vaccine dose.

Various vaccine experts have reported that, while the reductions are large, they are not as large as feared. Additionally they believe that better effectiveness against severe outcomes is likely to be retained because other parts of the immune system, such as T cells and B cells, are also able to intervene in the event of Omicron infection. Further real-world hospitalisation data, split by vaccination status, will be needed to determine effectiveness against severe outcomes.

Effectiveness of current treatments

In addition to corticosteroids and IL6 Receptor Blockers, monoclonal antibodies are effective treatments for existing variants. GlaxoSmithKline reported that their treatment has retained effectiveness against Omicron under laboratory conditions. However REGEN-COV (casirvirimab/imbedvimab) does not appear to be effective, based on laboratory results from Germany and consistent with a statement from Regeneron in late November.

Actions in the face of uncertainty

What actions should we be taking as we wait for further data, especially from South Africa which is further into the Omicron wave?

In our blog published earlier this year, we noted that how one frames the null hypothesis when answering the question “should we be worried about this variant?” will have a great impact on the resulting decision-making in the presence of lack of evidence.

Is the null hypothesis that Omicron will effectively have the same outcomes as Delta? In the absence of evidence showing that Omicron’s impact is different, we could decide to continue to act as we would with Delta until this null hypothesis is proved false.

Or is the null hypothesis that Omicron will be different and potentially more problematic than Delta? In the absence of evidence showing that Omicron’s impact is similar to Delta’s, we could decide to alter current policy to minimise risk until the null hypothesis is proved false.

James Ward, a mathematician who is active on Twitter, has used a stylised model to suggest that over 30% of the population could become infected with Omicron and that if this variant was half as severe as Delta, this would still lead to 80,000 Omicron-related hospitalisations in the absence of mitigating steps.

The WHO has recommended that countries:

- Enhance surveillance and sequencing of cases and share genome sequences on publicly available databases such as GISAID

- Continue to implement public health measures to reduce COVID-19 circulation overall

- Increase health capacity to manage an increase in cases

- Address inequities in access to vaccines, treatment and diagnostics.

In the next few weeks we will know Omicron better and be able to assign our own English adjectives to it.