Guest blog by Ariel Karlinsky

At the start of the pandemic, around March 2020, what began as whispers turned to shouts in some parts of the media – COVID is nothing major to worry about. It is just like the flu. If in ordinary times several hundreds of people die from the flu each month in Israel, the same number of people will die during COVID, with the cause of death simply changed from flu to COVID. The “evidence” for this was simple: March 2020 had almost the same number of deaths from all causes to March 2019. This interested me, so I started to investigate.

I am an empirical economist and I am used to conducting international comparisons. When you have information from many countries, over-simplified theories usually fail. If you closely examine the trends in one country, you can be fooled to believe that you have detected incredible empirical regularities in action, whether it is about unemployment, COVID or excess deaths. So I wanted to check were there any excess deaths in other countries, and if so, how many?

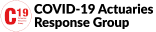

Excess deaths are a tried and true method to gauge the impact of pandemics, natural disasters, famines and other disasters. It is the number of deaths above and beyond what is expected in ordinary times based on historical data. There are many methods to compute the expected, and thus excess, number of deaths. For example, a lot of institutions and publications use the average number of deaths in the previous 3 or 5 years. This is a good estimate in countries where the number of deaths doesn’t vary much by year (such as the UK) but it will lead to over-estimating excess deaths where deaths increase by year (such as South Korea and the US) and under-estimating excess deaths where deaths decrease by year (such as Russia and Sweden).

For this reason, our estimate of the expected number of deaths accounts both for seasonality and the yearly trend in each country. However estimates are made, they require data on the historical number of deaths by week or month and on the current (or at least up to 2020) number of deaths. Data richness varies by country and for reasons of practicality and timeliness, the trend is captured via a simple linear function that allows implicitly for changes in the population size and profile.

I was a bit surprised, since this is not what I usually study, that almost no such data existed. Information on the number of deaths by country is usually compiled annually and with a significant delay, so there was very little “real-time” information. One by one, many countries have started to speed up their collection and publication of the number of deaths by week or month, and providing historical data, to be used as a baseline. Media and academic institutions such as The Financial Times, The Economist and the Human Mortality Database first headed this effort, collecting data from many locations in a single place.

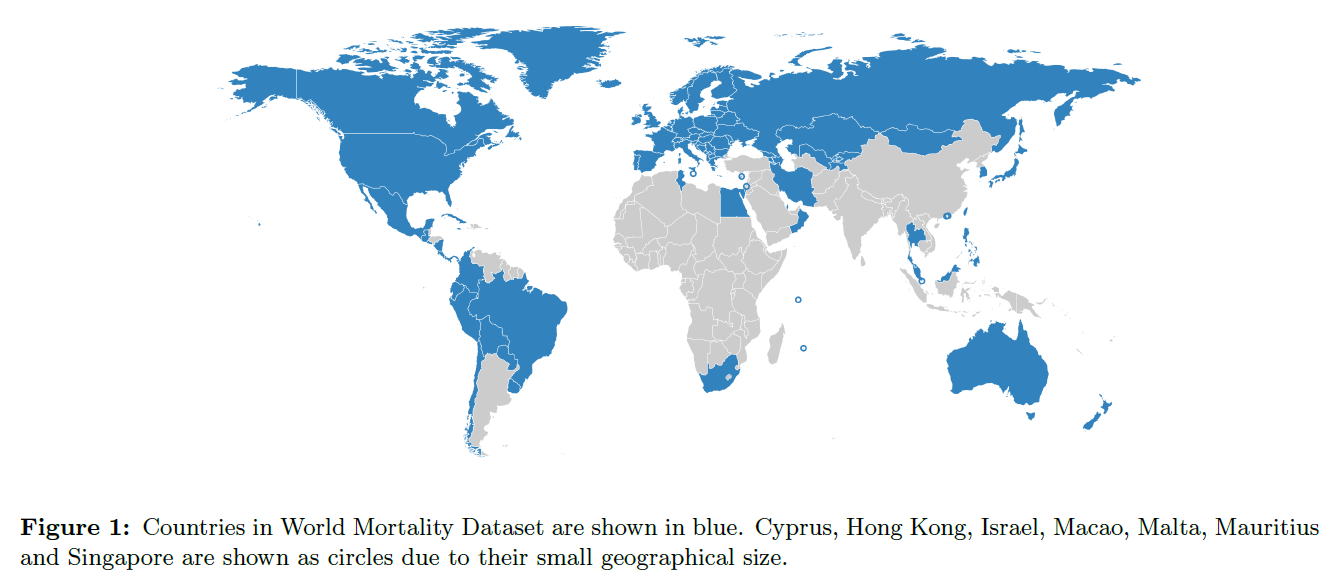

These early efforts showed early on large excess mortality in many of the hard hit countries such as the US, UK, Italy, Belgium etc. However, these collections were mostly constrained to high-income countries. I started investigating, looking for all-cause mortality data around the world. In many countries, it was hidden in plain sight: monthly statistical reports by countries, on some sub-table a few pages after the report on the consumer price index. If I didn’t find this I contacted the national statistical office, population registry or ministry of health of each country. Some have replied with the requested information, some haven’t replied at all and some, mostly in Africa, have replied that they simply do not have proper registration of deaths and they hope to have such capacity in a few years.

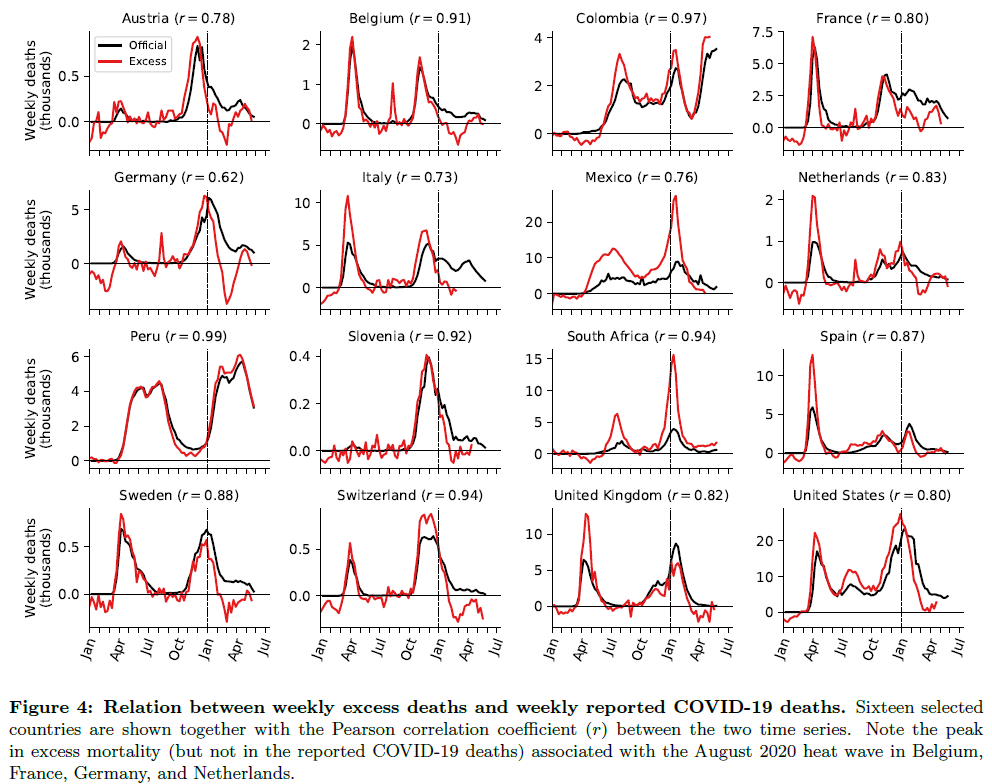

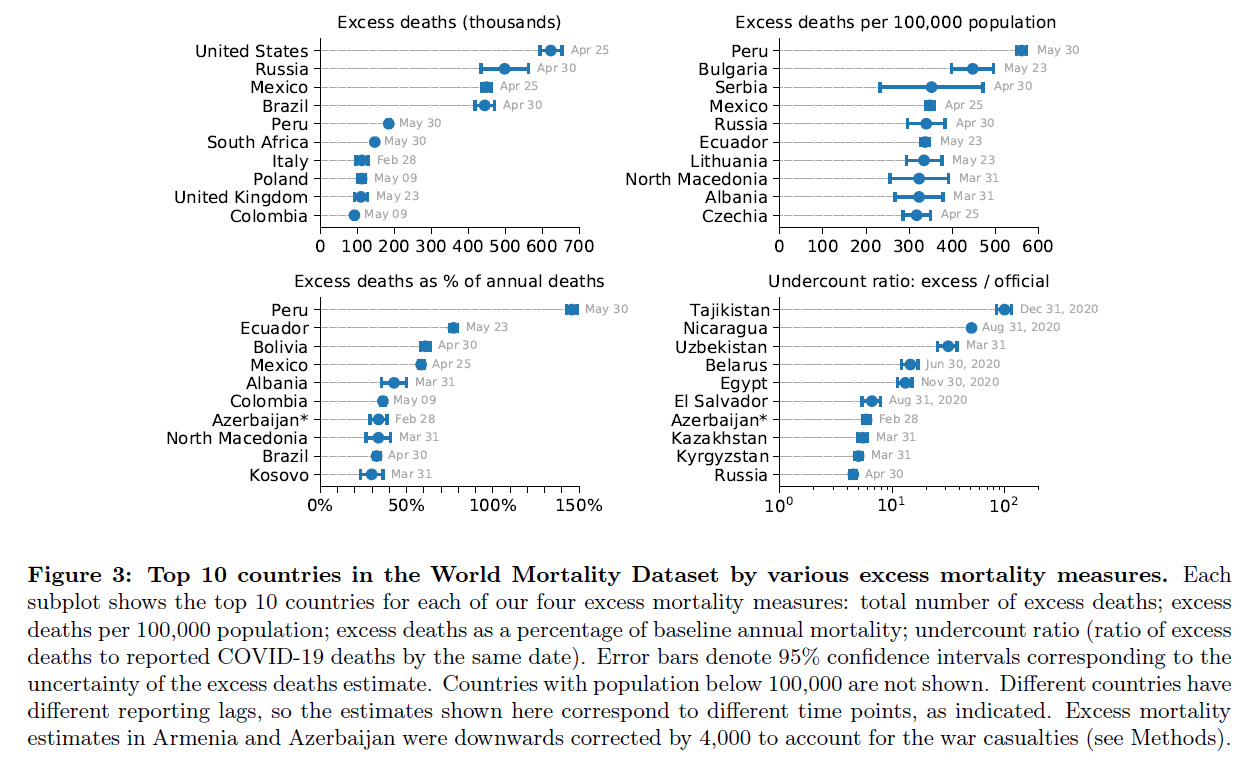

One by one, my colleague Dmitry Kobak and I added countries and territories to our collection, which currently includes 95 countries and territories. It is open to use by anyone and for anything as the World Mortality Dataset. An analysis of excess deaths using our dataset reveals that in high-income countries, excess deaths and COVID deaths have largely moved in tandem, dispelling rumors of nefarious greedy doctors and hospitals claiming large amounts of deaths as COVID due to some perverse financial incentive!

In low to middle-income countries, the situation was more complex – with excess deaths many times higher than reported COVID deaths. There are several reasons for this – in some, it is simply a lack of capacity. It is hard to certify deaths as resulting from COVID if the country lacks infrastructure to test. Examples include Peru and Ecuador, where excess deaths were about 2.5 times higher than reported COVID deaths. In some, there seems to be direct manipulation of the reported number of COVID deaths in order to convey a much brighter picture to the world. Examples include Tajikistan, Nicaragua, Uzbekistan and Russia, where excess deaths were 100, 50, 30 and 5 times higher than reported COVID deaths.

Reaching a global estimate of the number of excess deaths is hard, since we were unable to obtain data for many countries in Africa and for the largest countries in the world such as China, India and Pakistan.

This project would not have been possible without efforts, help and contributions by journalists, researchers and ordinary people from around the world, which we reached out to or have reached out to us to help us obtain information and resolve difficulties and questions we had about the reliability of information from across the world. This was and still is an iterative process, which gets better through time. A good example for this is Brazil, which has several official sources that report all cause mortality, but a naïve analysis of this can lead to wrong results. When we started, it was clear to us that this information had some issues, which we were not sure how to deal with. Brazilian researchers Marcelo Oliveira and Otavio Ranzani, who had much better knowledge of these sources, helped us understand and combine them to get at the best available real-time mortality monitoring in Brazil which, as in many other places, shows a large amount of excess deaths.