Vaccine effectiveness statistics attract a significant amount of attention. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) produces a weekly “COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report”. The report includes references to studies that have assessed vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic disease and severe outcomes. It also includes tables of cases, hospitalisations and deaths split by vaccination status for a recent four-week period.

The studies are designed to correct for biases. For example, some studies use a test-negative case-control design whereby vaccine status is compared between cases that test positive versus matched control cases that test negative. In this case, the study population is adults who had a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, with those testing negative acting as controls.

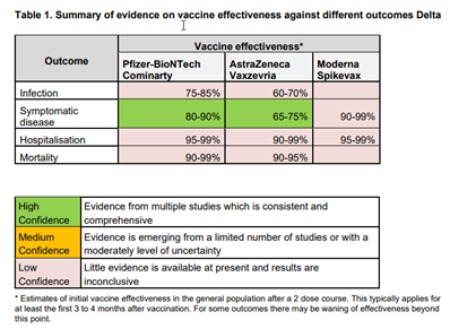

Also included in the report is comprehensive data on effectiveness of vaccines. Effectiveness against any symptomatic disease is shown to be 65% or higher against in the presence of the Delta variant. Effectiveness against severe outcomes appears to be 90% or higher (though there is less evidence available to date).

The tables with the event counts in recent weeks are appealing because the data is recent and the user has some control over how they drill into the figures. Unfortunately it is easy to reach incorrect conclusions because key pieces of information are unknown, in particular population denominators. The data is also not sufficiently detailed to correct for other biases. In this blog we focus on the issue with denominators. In fact the UKHSA report authors specifically point out that “interpretation of the case rates in vaccinated and unvaccinated population (sic) is particularly susceptible to changes in denominators and should be interpreted with extra caution.”

What’s the Problem?

So why is there an issue with denominators? The immediate answer is that England does not have a single reliable source for population estimates.

The mid-year population estimates produced by the ONS use the most recent published census, combined with other data sources for births, deaths and migration. The last census with published figures was in 2011 so the estimates may have drifted away from the true figures over time.

NHS England established the National Immunisation Management System (NIMS) in order to co-ordinate the COVID-19 vaccine roll out. This system obtains names, contact information, other personal details and GP registration information from NHS England’s Primary Care Registration Management service database. When a vaccine is given, this information is stored on the relevant patient’s record on the NIMS system. UKHSA establish vaccination status for cases, hospitalisations and deaths by linking to this system using each patient’s NHS number.

The UKHSA dashboard shows vaccine take-up based on the number of people registered on the NIMS system. The UKHSA vaccine surveillance report also uses the NIMS denominator. This data set is, in theory, more current than ONS population estimates. However, it is thought to significantly over-estimate the population because patients aren’t reliably deregistered when they move, for example if they leave the country.

We have a reliable count of the vaccinated population because the administered vaccines are recorded directly into NIMS. The size of the unvaccinated population is estimated from the difference between the estimated total population and the known vaccinated population. The estimate is only reliable if the total population estimate is reliable.

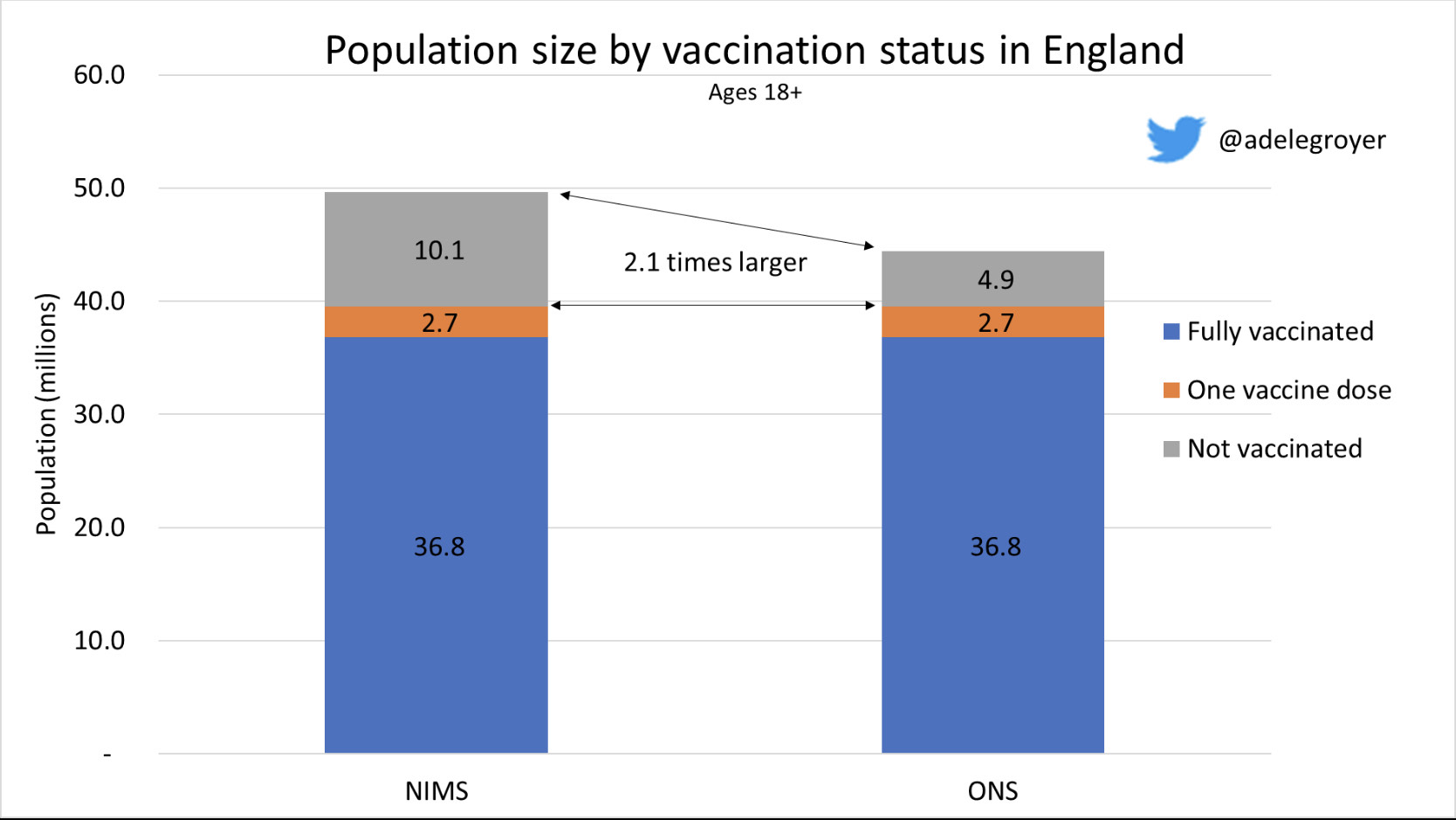

The ONS mid-2020 population estimate of adults aged 18 or older in England is 44.5m. In contrast, NIMS has 49.7m adults aged 18 or older. Using NIMS rather than ONS produces an unvaccinated population estimate that is over 2 times higher (10.1m vs 4.9m) if we consider vaccination status as at 18 September 2021.

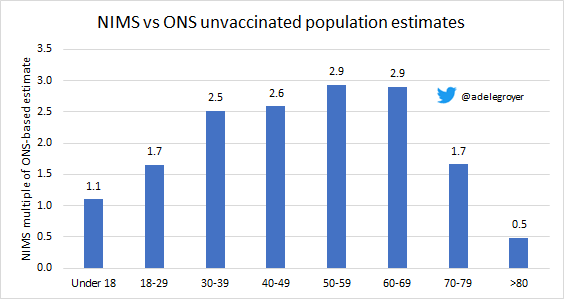

This effect is most pronounced at younger ages where the population is more mobile. In some age groups, the NIMS estimate for the unvaccinated population is almost three times higher than an estimate based on the ONS total population estimate. In contrast, for ages 80 and older the NIMS population estimate is higher and possibly more plausible than the ONS mid-2020 population estimate given what we know about how many people have in fact been vaccinated.

Why Denominators Matter

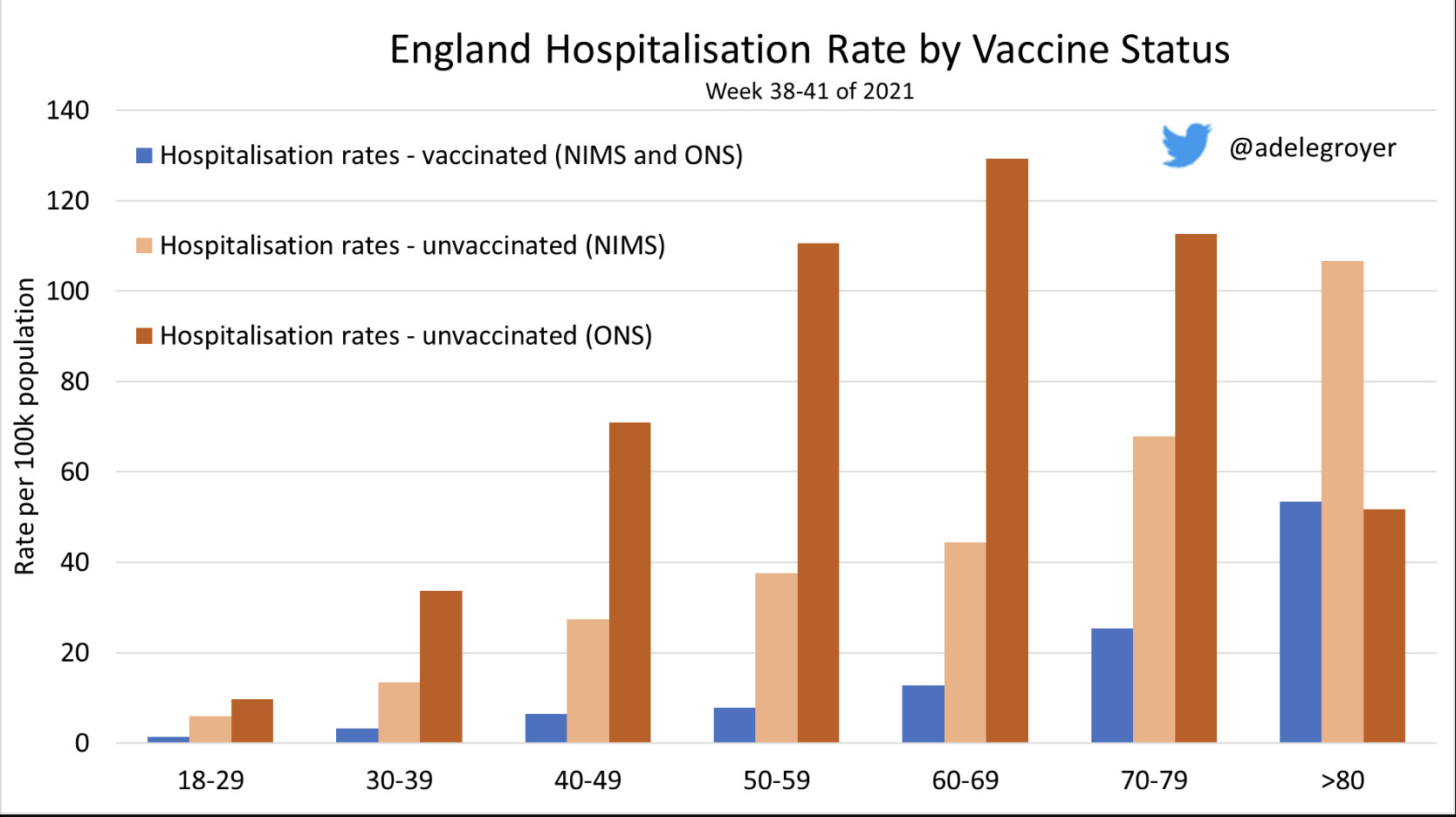

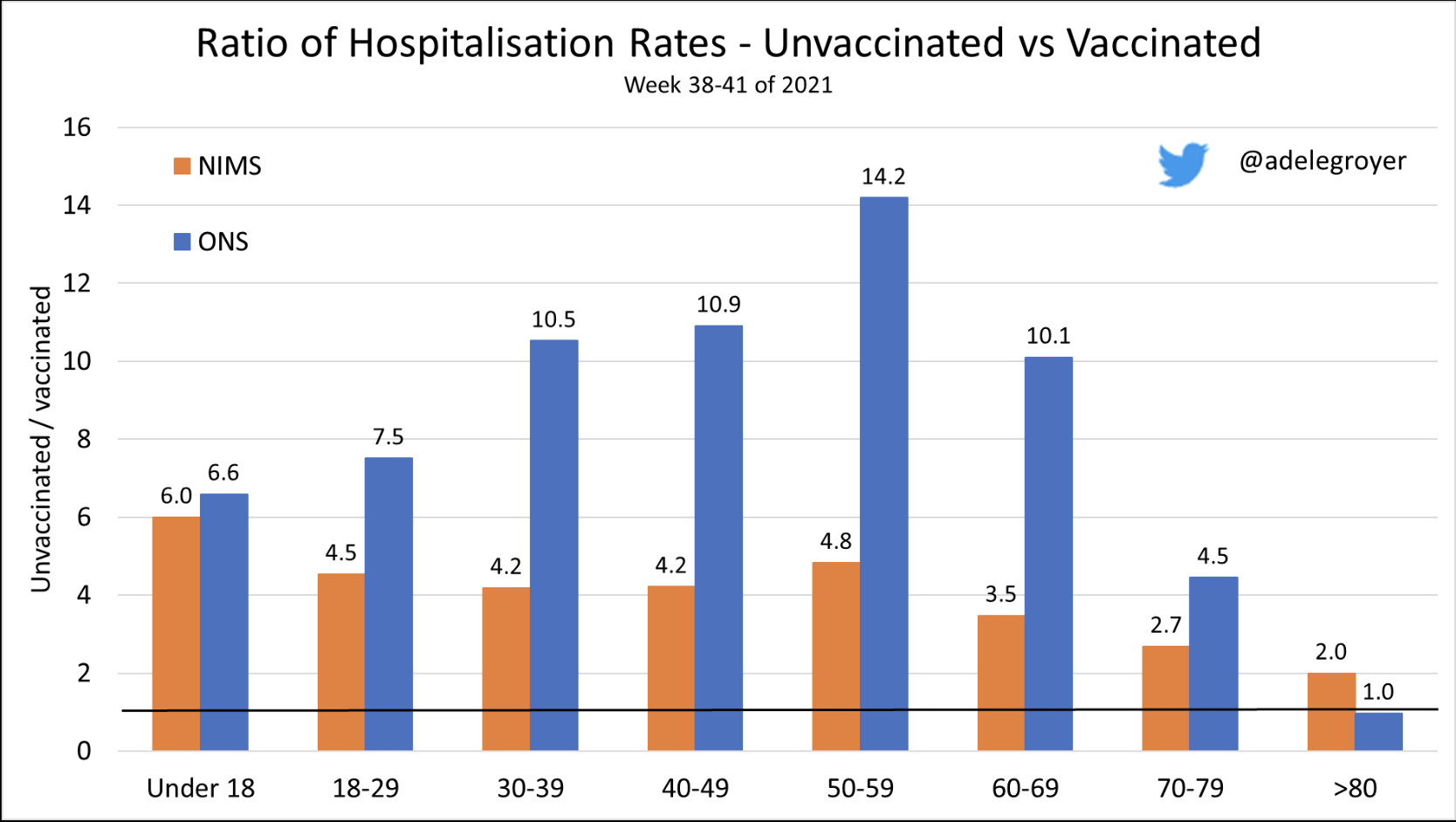

Uncertainty over the denominator affects the rate that we are measuring – if the denominator is twice as big, the rate will be halved. This has a big impact on measures like hospitalisation rates for the unvaccinated which are higher for all ages below 80 if one uses the ONS estimate of the total population instead of the NIMS estimate used by UKHSA in their reports. The reverse is true for ages 80 and older.

The problem is accentuated when a comparison is made with the vaccinated population, where there is certainty over the denominator. Using the NIMS population estimate, hospitalisation rates for the unvaccinated are 2 to 6 times higher than the corresponding rates for the fully vaccinated population, depending on age. If we use the ONS population estimate, the unvaccinated hospitalisation rate is 10 times higher in many age groups, which is more consistent with the 90% or higher effectiveness found in the case-control studies.

Infection Rates are Misleading

We’ve focused on hospitalisations, where high vaccine efficacy means that even with the uncertainty described, rates for vaccinated individuals are usually better on either measure than for the unvaccinated. However, for “cases”, where vaccines are effective but to a lesser extent than for severe outcomes, the uncertainty means that using NIMS data can even suggest that the unvaccinated have lower risk of being infected. Unfortunately this is leading to both misinterpretation and deliberate misuse of the data presented. We have seen high profile examples, both in the UK and overseas.

Conclusion

The level of data availability and transparency in the UK is phenomenal, and we acknowledge the skill and effort of those involved in its preparation. However, when results on high profile topics are very sensitive to assumptions that are not easily resolved, care is needed in presenting this information to avoid the risk of misleading both domestic and overseas audiences.